A look at the early history of Wonder Elementary School

The fight to give an equal education to everyone more than half a century ago

news@theeveningtimes.com

[ Editor’s Note: Portions of this article are from the October 12, 1949 issue of “ Life” Magazine in the article titled: “ West Memphis School – Editor fights for an education for 1,000 Negroes”]

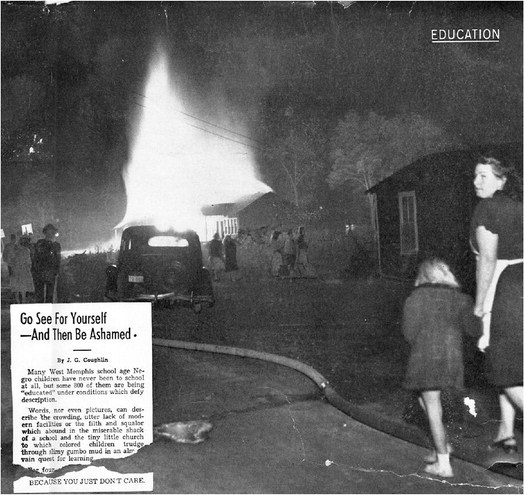

The night the Negro school burned down there was a red glow in the sky and a clanging of fire enegines in West Memphis, Ark. The school was just a 10room frame building; it burning like kindling, and half of it was destroyed.It was the only school for the town’s 1,000 Nergo children. Jack Coughlin (right), edtior of the West Memphis News, ran the picture above in his paper and sat back to see what the town was going to do about another school.

Last September, 10 months after the fire, the town opened a new $300,00 school_ for white children.

Now its 900 white children had two school and one of the finest system in the state. But the Negro children still had no school at all. Some of them jammed into a small church floating in a sea of mud. Some went across the river, gave false addresses and went to school inTennessee. The rest just quit school.This was more than Editor Coughlin could stand. In a series of hot editorial(above) he began belaboring the townspeople, but all they did was talk about a new school and patch up the halfburned building. It has coal stoves and no eletric lights, but 310 students and five teachers can fit into its five small rooms. Another 370 are still crammed in a one-room church. They call the five-room school “Wonder” after West Memphis, which which like to be known as the Wonder City.

In September 1999 the Life Magazine did update on Wonder School, in an article by Rick Bragg featuring photographs by Andrew LIchtenstein. From the article: The photograph tugs you into its sadness, as if it were more than a two-dimensional image burned onto paper a half century ago. It is of children, mostly, more than 300 of them, packed into pews and stright-back chair in a makes shift classroom in the ragged sanctuary of black church, short legs dangling over the slime of Arkansas gumbo mud that coats the floor. A cast-iron stove, the only heat, squats in the center of a room without electric light or running water. Rising above the sea a faces, a solitary teacher stand tall and stiff, as if determined to teach the children something even if it is 1948 in West Memphis, Ark., a place that allocates $144.51 per year to educate a white student and $19.51 per year to educate a black one even if she has to write down her lesson with scrap chalk plucked from a box of worn-down nubs left over from the white schools.

She appears if the blackboard is any sign to be trying to teach the younger students to count to 100, though she is losing the battle this day, this moment.

Most of the eyes here seem locked on the LIFE magazine photographer, who although invisible in the print itself, is mirrored in those questioning eyes. It is the first camera many of them have ever seen.

One little girl stares rapt, her open mouth caught in an unspoken question. On her lap is a younger child five or so, who does not seem impressed at all. Her head, crowned by a white ribbon, is bowed eyes fixed on single sheet of paper. Like the tall teacher who seems determined to teach, she seem determined to learn. It couldn’t go on like that forever, of course. Hearts had to soften sooner or later, or at least have their brittle casing cracked open by conscience. In West Memphis is those day, the hammer belong to a crusading newspaper editor named Jack Coughlin, who pounded at the power brokers in West Memphis with a series of editiorials in his West Memphis News. “Go see for yourself, and then be shamed,” he wrote. “Words nor even pictures, cannot descride… the miserable shack of a school… to which children trudge through slimy gumbo mud in an almost vain quest for learning….BECAUSE YOU JUST DON’T CARE.”

White friends abandoned him, but Jack Coughlin kept pushing, winning over the president of the chamber of commerce and then the mayor’s wife.

Finally in 1950, as black students marched with sign that siad PLEASE and a handful of black voters risked their safety in that rigidly segregated times to cast votes for a bond issue,West Memphis said yes to new black school for grades one through 12. It was a $150,000 apology to the children in that sad photograh. They called it simply, the Wonder School, which made perfect senes to everybody who had been in the old one.

The girl, the one with the ribbon in her hair, was there when they opened the doors She still is.

Share